Hawa Kassé Mady Diabaté

Program Notes

Tegere Tulon (2018)

I. Funtukuru

II. Dulen

III. Kalime

IV. Wawani

V. Janety

Hawa Kassé Mady Diabaté

(b. 1974)

Composed for

50 For The Future:

The Kronos Learning

Repertoire

Arranged by Jacob Garchik

(b. 1976)

About the work

Tegere Tulon revisits the handclapping songs of Hawa Diabaté's childhood, which were such formative experiences for her, and which are gradually dying out except in remote villages. Performed exclusively by girls outdoors in a circle, usually on moonlit nights, the handclapping songs are normally very short, consisting of one or two phrases repeated in call and response, often involving counting, each one with its own dance. Children make them up spontaneously, using the rhythms of language to generate musical rhythm, with playful movements, some individual, some coordinated by the whole circle.

Building on her own memories of the handclapping songs she used to do as a young girl in Kela, Hawa has created four new pieces in handclapping style, which she hopes will encourage Malians not to abandon this rich cultural heritage. The lyrics are humorous and poignant—they talk about the importance of family, the teasing relationship between kalime“cross-cousins” (a man’s children and his sister’s children are cross-cousins), a girl who loves dancing so much she falls into a well and then climbs out, and how long it takes to get to Funtukuru, her husband’s village, where she went to film handclapping.

1. Funtukuru. This song is made up of three short call and response songs whose lyrics are built around counting, which is a characteristic component of the tegere tulon tradition. It was inspired by a trip to film handclapping songs in Funtukuru, a village located deep in the rolling savannah countryside of western Mali, where Hawa’s husband, Demba Kouyaté, is from. Funtukuru is inhabited almost entirely by Mande jelis (griots, or hereditary musicians), and they carry on traditions that are mostly lost in the bigger towns and cities of western Mali, including tegere tulon.

The song plays on the name of the village, which is made up of two words in Maninka (the main language of the region). “Funtu” means “to arrive” and “kuru” means “hill”. Funtukuru is indeed surrounded by hills of big red boulders that rise sharply out of the earth.

To get to Funtukuru, you drive northwest from Bamako, Mali’s capital along a pot-holed road for 170 kms, passing through the historic town of Kita – a place famous for its music- and then onwards down a dirt road for another 30 kms, past cotton fields and many small villages. It’s a long and dusty journey, along which our car had several breakdowns. So the song celebrates our arrival there in the late afternoon, where we were treated to some truly wonderful and creative handclapping dance-songs, which astonished even Hawa.

The rest of the song is about a tall girl called Marama who loves dancing so much that she falls into a well, but then somehow climbs out and carries on dancing; she is fearless, even in front of a host of men. This is Hawa’s playful reflection on the joy of handclapping songs. It is her way of encouraging girls—who are the ones that perform the tegere tulon—not to be put off by the stern gaze of male elders.

2. Dulen. Mali is a predominantly Muslim society, where a man can take up to four wives, according to the holy Quran. Children by different mothers are considered rivals, while children by the same mother are seen as having a harmonious relationship, known as badenya in Bamana, the main language of southern Mali.

Hawa is herself the daughter of a polygamous marriage, and a member of a vast extended family of griots, many of whom are recognised as some of the most important musicians of the 20th century and even further back into pre-colonial times. She is very aware of the importance of solidarity in families, which she evokes in this song through the example of badenya. An added factor in this that when a couple gets married, traditionally the bride goes to live with her husband’s family, and her in-laws do not always treat her as they would their own daughter.

Hawa explains that in this, she exhorts the new husband through metaphor and flattery to treat his new wife as if part of his own kin. Without actually saying so, she compares the husband to the cool, protective shade of a tree—it is long-lasting and beneficial, and should be celebrated (yogobe ko). She then refers to him as ‘fine soap’—a cherished commodity in villages of the savannah of West Africa.

Musically, the structure of this song uses a kind of mirror image that is found in many of the oldest song styles in the region. The verse of these songs has four lines: ABCD. The solo voice takes A, the chorus responds with B, the soloist sings C and D. Then they swap roles: The Chorus sings line A, the soloist responds with B, and the chorus sings lines C and D.

With this mirrored structure, the young girls who are doing the handclapping songs learn to perform all the lines with equal confidence, and the texture is continually varied.

3. Kalime. Kalimè is a word in Maninka (Hawa’s mother tongue) that refers to a very specific type of first cousin, which in anthropological terms is known as “cross-cousin”. When a brother and sister each have children, those children are first cousins. But they are considered different from cousins who are related through two sisters or two brothers. In southern Mali, the kalimè relationship is accorded a special status which is demonstrated in particular ways that are played out humorously in the handclapping songs. This is the basis for Hawa’s third piece for the Kronos Quartet.

When a male kalimè cousin gets married, his female kalimè cousins are supposed to show in a light-hearted way just how well he has treated them and how much they hold him in esteem. At the celebratory party for the wedding, there is a specific kalimè dance they will perform. This consists of tying a scarf around their waists leaving a floppy bow in back, which they then wag or fan like a bird’s tail in rhythm to the music. At one point, they also fall on the floor and dance facing down, much to the delight of everyone present—this is meant to show that their male cousin has been so generous and hospitable that they have seriously overeaten, and have toppled over because their stomachs are so full.

These dances are performed with great amusement and gusto, and of course, the male kalimè cousin is then supposed to reward them with more food and other gifts. Thus, the special type of cross-cousin relationship is reinforced and played out for everyone to see. Hawa has composed this handclapping song to honour this wonderful tradition. She uses the evocative minor pentatonic scale of central Mali to do so.

4. Wawani. Wawani is an onomatopoeic term in Maninka for the sound that people make when celebrating. Hawa describes this song as a ‘sewa tulunke”, a song for entertainment and enjoyment, specifically aimed at neighbours. It is in two parts. The first is about the importance of solidarity and understanding, whether between family members, friends or neighbours. The second is in praise of a particular type of person known as ‘soma’, who has special mystical powers and is wise, a kind of wizard, but also feared and misunderstood. In pre-colonial times, the term soma (sometimes translated as “sorcerer”) was often synonymous with kingship, since rulers were believed to have esoteric power. Hawa advises people not to reject such a person, since they have the gift of bringing good things to the world; she compares the soma to the Prophet Musa (Moses). The name Musa is considered so powerful, that it is normally referred to by the nickname Bala (porcupine).

5. Janety. In the fall of 2021, Hawa was invited to create a fifth handclapping song to celebrate Kronos’ executive director Janet Cowperthwaite and her 40th year with the Kronos Quartet. The resulting praise song, “Janety,” is a version of Soliyo, a very archaic song, with stock formulaic phrases around calling horses for the king to ride on ("the person who has a jeli (griot) is better than the person who has no jeli.” Roughly translated, the praise song says:

Janety, I call the horses for you.

Truly important people don't walk, they ride on horseback.

Janety, you have no equal. You are unique. We will visit you in San Francisco, city of hope.

Forty years! 'San bi nani!' - Janet & Kronos Quartet.

Janety - may God give you long life and good health.

Happy anniversary!

In Bamako, Diabaté first recorded the composition of Tegere Tulon on vocals with members of her family, accompanied by her two sons on acoustic guitars. The recordings were then transcribed and arranged for string quartet by Jacob Garchik. Hear Diabaté’s original recordings here >>

Tegere Tulon: Handclapping Songs from Mali

For her 50 for the Future commission, Hawa decided to revisit the handclapping songs of her childhood, which were such formative experiences for her, and which are gradually dying out except in remote villages.

Film by Professor Lucy Durán and Moustapha Diallo, with editing help from Darryl Jones (darryljonesfilms.com)

Selected for the 2021 Festival International du Film PanAfricain de Cannes.

When you're in Hawa's presence, you smile. You want to do your best, and you also want to have fun, especially when you're performing her music. I'd recommend watching her videos, listening to her recordings—be around her as much as you can. Something wonderful and joyous will rub off that will influence how you play her piece.

Artist’s Bio

Hawa Kassé Mady Diabaté

Mali

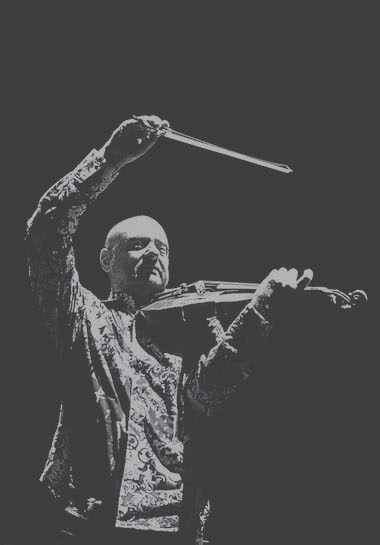

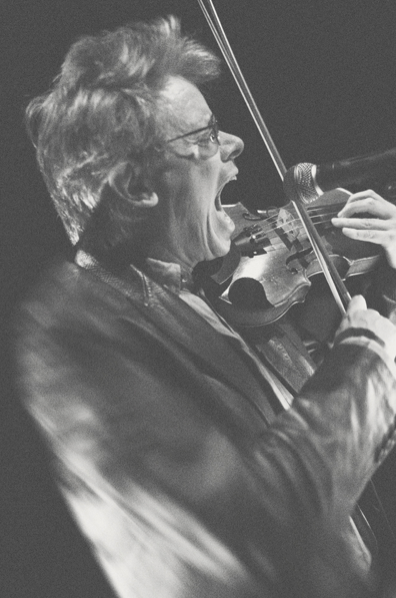

Hawa Kassé Mady Diabaté possesses one of the most beautiful, versatile, and expressive voices of West Africa. A jelimuso (female jeli or ‘griot’) from Mali, she has acquired a cult following as the charismatic singer of Trio Da Kali, an acoustic trio which was formed by the Aga Khan Music Initiative specially to collaborate with the Kronos Quartet. She has received rapturous reviews for her work on Kronos and Trio Da Kali’s collaborative award-winning album Ladilikan and for her moving performances with Trio Da Kali, who have toured widely in Europe and the US to critical acclaim.

Diabaté’s charismatic voice is emphatically 21st century, but it is also steeped in the rich heritage of Mali’s griots, the hereditary musicians that date back to the founding of the Mali Empire in the 13th century. She was born into a celebrated griot family, the Diabatés of Kela, a village in southwest Mali famous for its music. The Kela Diabatés have a formidable reputation as singers, instrumentalists, and reciters of oral epic histories, with many legendary names from the pre-colonial era to the present, and today Hawa is the torch bearer of that great tradition.

Diabaté’s father Kassé Mady Diabaté was known for his entrancing singing, moving his listeners to tears—from which he gets his nickname, Kassé, ‘to weep’—a quality that Hawa has inherited, along with the nickname. Her great-aunt was Sira Mory Diabaté, considered the most important Malian female vocalist of the 20th century, a prolific composer whose songs, like “Kanimba” (on the album Ladilikan) have become griot classics.

Settling with her family in Bamako, the capital, in her teens, Diabaté began performing on the wedding party circuit, where she remains much in demand. Apart from one cassette released on the local market, she only ever recorded with her father, in the chorus of his album Kassi Kasse (2003), recorded on location in Kela. The power and beauty of her voice shone through the album, which won a Grammy nomination. But it was not until Trio Da Kali was formed that Diabaté’s remarkable singing would find a platform in its own right.

Support Kronos’ 50 for the Future

Help support Kronos’ 50 for the Future as we commission fifty new works designed expressly for the training of students and emerging professionals.

In Tegere Tulon, Hawa shows us the amazing ways in which music can be absorbed and passed down through the generations. There's a sense of responsibility to teach the younger people, which falls right in line with the goals of Fifty for the Future. It's our responsibility to give not only our audiences but other players some of the same opportunities we've had, and I feel like Hawa does that perfectly here.